Containers

Contents

Containers¶

Why Containers?¶

Even for moderately complex projects, the size of the software dependency stack can be huge.

Take a simple pipeline to build a pdf report for an analysis scripted in R using Rmarkdown, for example.

To make this reproducible, not only do (i) the respective R packages need to be installed and (ii) the R version needs to be the same, but also (iii) the versions of pandoc and LaTeX need to be the same as during runtime.

Instead of trying to resolve these dependencies via a package manager (such as conda) - which also depends on all required software being available in a single package manager - it might be easier to create a snapshot of the entire computing environment including all dependencies. These computing environments are then self-contained, hence the name ‘containers’.

What are Containers?¶

Containers allow a researcher to package up a project with all of the parts it needs - such as libraries, dependencies, and system settings - and ship it all out as one package. Anyone can then open up a container and work within it, viewing and interacting with the project as if the machine they are accessing it from is identical to the machine specified in the container - regardless of what their computational environment actually is. They are designed to make it easier to transfer projects between very different environments.

In a way, containers behave like a virtual machine. To the outside world, they look like their own complete system. However, unlike a virtual machine, rather than creating a whole virtual operating system plus all the software and tools typically packaged with one, containers only contain the individual components they need in order to operate the project they contain. This gives a significant performance boost and reduces the size of the application.

Containers are a particularly useful way for reproducing research which relies on software to be configured in a certain way, or which makes use of libraries that vary between (or do not exist on) different systems. In summary, containers are a more robust way of sharing reproducible research than package management systems or Binder because they reproduce the entire system used for the research, not just the packages explicitly used by it. Their major downside is that due to their greater depth, they are conceptually more difficult to grasp and produce than many other methods of replicating computational environments.

Ben Corrie give a reasonably accessible overview of core concepts in ‘What is a container?’.

What are Images?¶

Images are the files used to generate containers. Humans do not make images; they write recipes to generate images. Containers are then identical copies instantiated from images.

Think of it like this:

A recipe file a human writes contains all the steps to generate a working version of the project and its computational environment, but no actual materials. Think of this as a blueprint.

Building an image takes that recipe and using it, assembles all the packages, software libraries, and configurations needed to make the full-fledged project and environment, and bundles them up in a condensed lump. Think of images like a piece of flat-pack furniture made using the blueprint.

Containers take that image and assemble a fully working version of the project and the environment needed to run it. Think of this as assembling the flat-pack furniture.

So if a researcher wants to allow others to reproduce their work, they would need to write a recipe file, and use it to build an image of their project. They can then share this image file with anyone who wants to replicate their work. That person can then use the image to generate a container containing a working version of the project.

What is Docker?¶

There are many tools available for creating and working with containers.

We will focus on Docker, which is widely used, but be aware that others such as Singularity also exist.

Singularity is sometimes preferred for use on high-performance computing systems as it does not need sudo permissions to be run, while Docker does.

In Docker, the recipe files used to generate images are known as Dockerfiles, and should be named Dockerfile.

Docker Hub hosts a great many pre-made images, such as images of Ubuntu machines, which can be downloaded and build upon. This makes the process of writing Dockerfiles relatively easy since users very rarely need to start from scratch, they can just customise existing images. However, this leaves a user vulnerable to similar security issues as described in the Security Issues of the YAML sub-chapter:

It is possible to include malicious code in Docker images

It is possible for people producing images to unknowingly include software in them with security vulnerabilities

This article goes deeper into the potential security vulnerabilities of containers and here is a detailed breakdown of security features currently within Docker, and how they function. The best advice for using images built by others is, as usual, only download and run something on your machine if it comes from a trusted source. Docker Hub has “official image” badges for commonly used, verified images as shown here:

Installing Docker¶

Installers for Docker on a variety of different systems are available here. Detailed installation instructions are also available for a variety of operating systems such as Ubuntu, Debian, Macs, and Windows.

Key Commands¶

Here are a few key commands for creating and working with containers:

To build an image from a Dockerfile, go to the directory where the Dockerfile is and run:

sudo docker build --tag image_name .

To list the images on your system, use:

sudo docker image ls

To remove an image, run:

sudo docker rmi image_name

To open a container from an image, run:

sudo docker run -i -t image_name

The

-i -tflags automatically open up an interactive terminal within the container so you can view and interact with the project files.To exit an interactive terminal, use:

exitTo get a list of active containers with IDs, run:

sudo docker container ls

There are also three main commands used for changing the status of containers:

Pausing suspends the process running the container.

sudo docker pause container_ID

Containers can be unpaused by replacing

pausewithunpause.Stopping a container terminates the process running it. A container must be stopped before it can be deleted.

sudo docker stop container_ID

A stopped container can be restarted by replacing

stopwithrestart.If

stopdoes not work containers can be killed usingsudo docker kill container_ID

To remove a container, run:

sudo docker rm container_ID

Writing Dockerfiles¶

Let us go through the anatomy of a very simple Dockerfile:

# Step 1: Set up the computational environment

# Set the base image

FROM ubuntu:18.04

# Install packages needed to run the project

RUN apt-get update && \

apt-get install -y --no-install-recommends python3.7 python3-pip && \

rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

RUN python3 -m pip install numpy

#-----------------------

# Step 2: Include the project files in the image

# Copy files from the `project_files` directory on the machine building the image

# into the `project` folder in the container. This folder and any missing

# directories in its path are created automatically.

COPY project_files/ project/

This looks complicated, but most of the lines in this example are comments (which are preceded by #’s).

There are only six lines of actual code.

The first of these is a FROM statement specifying a base image.

All Dockerfiles require a FROM, even if it is just FROM SCRATCH.

All the following commands in a Dockerfile build upon the base image to make a functioning version of the researcher’s project.

Specifying a version for the image (18.04 in this case) is optional.

However, it is best practice as it ensures that our Dockerfile remains valid after new releases of Ubuntu, which may not include packages (or specific versions thereof) that we require later (for example python3.7).

It is worth spending time to choose an appropriate base image, as doing so can reduce the amount of work involved in writing a Dockerfile dramatically. For example, a collection of images with the R programming language included in them can be found here. If a project makes use of R, it is convenient to use one of these as a base image rather than spend time writing commands in your Dockerfile to install R.

The biggest block of lines comes next.

It’s a series of RUN statements, which run shell commands when building the image.

In this block, they are used to install the software necessary to run the project. The first RUN block is a

chain of commands of this form:

RUN command_to_do_thing_1 \

&& command_to_do_thing_2 \

&& command_to_do_thing_3 \

&& command_to_do_thing_4

It is good practice to group related commands into a single RUN block to reduce the final size of your image by

avoiding the creation of unnecessary layers.

We also follow best-practice by using --no-install-recommends to avoid installing unnecessary packages

and cleaning up the apt-cache, both of which further reduce the size of Debian or Ubuntu images.

After we have installed Python, we use another RUN statement to install a library required by our code.

Finally the COPY command is used to copy the project files from the machine building the image into the image itself.

The syntax of this command is COPY file_to_copy location_in_container_to_copy_to.

In this example, all the files in the project_files directory are included in the project file in the container.

Note that you can only copy files from the directory where the Dockerfile is located, or subdirectories within it (in the example, that is the

project_files subdirectory).

The ADD command has the same capabilities as COPY, but it can also be used to add files not on the machine building the image.

For example it can be used to include files hosted online by following ADD with a URL to the file.

It is good practice to use COPY, except where ADD is specifically required, as the term COPY is more explicit about what is being done.

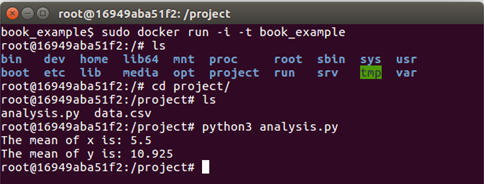

Here is what happens if a container is opened from an image called book_example, built from the example above:

As you can see, the directory project has been created, and inside the project files, analysis.py and data.csv have been copied into it.

Because the Dockerfile already includes the software required for the project, in the image, the analysis.py script runs without installing more software.

WORKDIR¶

This command can be used in Dockerfiles to change the current working directory.

Commands that follow this in the Dockerfile will be applied within the new working directory unless/until another WORKDIR changes the working directory.

When a container is opened with an interactive terminal, the terminal will open in the final working directory.

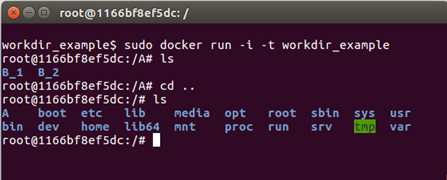

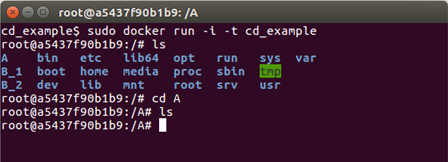

Here is a simple example of a Dockerfile that uses WORKDIR, and the container it generates.

# Basic setup

FROM ubuntu

RUN apt-get update

# Make a directory called A

RUN mkdir A

# Make the working directory A

WORKDIR A

# Make two directories, one called B_1 and one called B_2

RUN mkdir B_1

RUN mkdir B_2

Directories B_1 and B_2 have been created within directory A.

WORKDIR should be used when changing directories is necessary while building an image.

It may be tempting to use RUN cd directory_name instead, as this syntax will be more familiar to those that commonly work via the command line,

but this can lead to errors.

After each RUN statement in a Dockerfile, the image is saved, and any following commands are applied to the image anew.

As an example, here is what happens in the above example if the WORKDIR A line is swapped

for RUN cd A.

All the directories have are in the top level in this case, rather than B_1 and B_2 being inside A.

This is because the image was restarted after the RUN cd A command and opened at the top (root) level by default, so that is where the

mkdir B_1 and mkdir B_2 commands took effect.

Other Commands¶

Other commands that are sometimes used in Dockerfiles include:

CMD: This is used to run commands as soon as the container is opened. This is different to RUN commands which are commands run as part of setting up a container. For example, to have a welcome message when a container is opened from the image,CMDcould be used as follows:CMD ["echo","Welcome! You just opened this container!"]

It is good practice to use CMD for any commands that need to be run before someone starts working in the container instead of forcing users to run them themselves (and trusting that they will even know that they need to).

VOLUMES: These will be discussed later.MAINTAINER: This contains information regarding the person that wrote the Dockerfile. It is typically included at the top of a Dockerfile.EXPOSE: This includes ports that should be exposed. It is more relevant to people using Docker to share web apps.USER: Change the user that a command is run as (useful for dropping privileges).

Building Images and .dockerignore Files¶

As mentioned in the key commands section, to build an image open a terminal in the same directory as the Dockerfile to be used and run:

sudo docker build --tag name_to_give_image .

When an image is built everything in the Dockerfile’s directory and below (this is called the “context”) is sent to the Docker daemon to build the image.

The daemon uses the Dockerfile and its context to build the image.

If the context contains many large files, which are not needed for building the image, (old datafiles, for example) then it is a waste of time sending them to the daemon.

Doing so can make the process of building an image slow.

Files can be excluded from the context by listing them in a text file called .dockerignore.

It is good practice to do so.

The files do not need to be listed individually in the .dockerignore file.

Here is an example of the contents of a .dockerignore file:

*.jpg

**/*.png

data_files/*

file_to_exclude.txt

This excludes from the context:

All

.jpgfiles in the same directory as the Dockerfile fileAll

.pngfiles in the same directory as the Dockerfile file or any subdirectories within itAll files within the

data_filesdirectoryThe file named

file_to_exclude.txt

Sharing Images¶

Docker images can be shared most easily via Docker Hub, which requires an account. Say two researchers, Alice and Bob, are collaborating on a project and Alice wishes to share an image of some of her work with Bob.

To do this, Alice must:

Write a Dockerfile to produce an image of her work.

Build the image. She (being inventive) calls it image_name

Go to DockerHub and sign up for an account. Say Alice (again, being inventive) chooses the username

username_AliceLog into DockerHub via the terminal on her machine using:

sudo docker login

Tag the image of her project on her machine via the command line by supplying the name of the image and using the pattern

username/image_name:version. So Alice runs the command:sudo docker tag image_name username_Alice/image_name:version_1

Push the image to her Docker Hub account using:

sudo docker tag push username_Alice/image_name:version_1

Alice’s image is now online and can be downloaded. Over to Bob…

Bob (assuming he already has Docker installed) can open a container from Alice’s image simply by running

sudo docker run -i -t username_Alice/image_name:version_1

Initially, Docker will search for this image on Bob’s machine. When it does not find it, it will automatically search DockerHub, download Alice’s image, and open the container with Alice’s work and environment on Bob’s machine.

Copying Files To And From Containers¶

Containers act much like virtual machines; as a result, copying files into and out of them is not as trivial as copying files to different locations within the same computer is.

A file can be copied from the machine running a container into the container using:

sudo docker cp file_name container_ID:path_to_where_to_put_file/file_name

Recall that container IDs can be obtained using sudo docker container ls.

A file can be copied from within a container to the machine running the container by running the following command on the machine running the container:

sudo docker cp container_ID:path_to_file/file_name path_to_where_to_put_file/file_name

If the second part (the path_to_where_to_put_file/file_name) is substituted for a ., then the file will be copied to whatever directory the terminal running the command is in.

Volumes¶

Every time a container is opened from an image, that container is completely new. Say a container is opened, and work is done within it. Say a container is opened, and work is done within it. If that container is closed, and the image it came from is again used to start another container, none of that work will be in the new one. It will simply have the starting state described in the image.

This can be a problem if a researcher wants to work in a container over time. Fortunately, there is a way around this using volumes. Volumes store the work done within a container even after it is closed, and can be used to load that work into future containers.

To create/use a volume, run:

sudo docker run -i -t --mount source=volume_name,target=/target_directory image_name

You should give your volume a more descriptive name than volume_name.

A target directory is required; only work within this directory will be saved in the volume.

Once the researcher is done, they can close the container as normal.

When they come back to the project and want to continue their work, they only need to use the same command as above, and it will load the work contained in volume_name into the new container.

It will save any new work there too.

Below is a list of volume related commands:

To list volumes:

sudo docker volume lsTo delete a volume:

sudo docker volume rm volume_nameTo delete all unattached volumes:

sudo docker volume prune

If, when deleting a container, a -v is included after rm in sudo docker rm container_ID, any volumes associated with the container will also be deleted.

Singularity¶

Prerequisites: At present, Singularity only runs on Linux systems (for example Ubuntu). If you use macOS, Singularity Desktop for macOS is in “Beta” release stage.

A significant drawback of using Docker for reproducible research is that it is not intended as a user-space application but as a tool for server administrators. As such, it requires root access to operate. There is, however, no reason why the execution of an analysis should require root access for the user. This is especially important when computations are conducted on a shared resource like HPC systems where users will never have root access.

The singularity container software was introduced to address this issue. Singularity was created with HPC systems and reproducible research in mind (see [this](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DA87Ba2dpNM video). It does not require root access to run (only to build container images!), and thus enables HPC users to locally build container images before running analyses on a high-performance cluster, for example. As an added benefit, this makes it possible to use almost any software on an HPC system without having to bother admin staff with installing it.

Furthermore, since Docker is the most well-known containerization approach, singularity aims at maintaining compatibility with docker containers. This means that singularity can be used to run normal docker containers (without requiring root access!).

Singularity can be used to run Docker images or extend them by building new images based on docker containers as a base layer. For instance, we could use singularity to create a vanilla ubuntu container with a shell using the ubuntu docker image:

singularity shell docker://ubuntu

(type

exitto leave the interactive shell again).

Just as docker images are built using Dockerfile files, singularity containers are built from singularity definition files.

The process and syntax are similar to docker files, but there are subtle differences.

As a minimal working example, we can build a lolcow container based on the official ubuntu docker container image.

Put the following in a lolcow.def file (based on the Singularity documentation):

Bootstrap: docker

From: ubuntu

%post

apt-get -y update

apt-get -y install fortune cowsay lolcat

%environment

export LC_ALL=C

export PATH=/usr/games:$PATH

%runscript

fortune | cowsay | lolcat

This ‘recipe’ uses a docker image as a basis (ubuntu), installs a few apt packages, modifies a few environment variables, and specifies the runscript (which is executed using the singularity run command).

Details on the singularity definition file format can be found in the official documentation.

A container image can then be built (requiring root!) via:

sudo singularity build lolcow.simg lolcow.def

This will pull the ubuntu image from DockerHub, run the steps of the recipe in the definition file and produce a single output image file (lolcow.simg).

Finally the runscript is executed as

singularity run lolcow.simg

Ideally, you should see a nice ASCII cow and a few words of wisdom:

___________________________________

/ You will be called upon to help a \

\ friend in trouble. /

-----------------------------------

\ ^__^

\ (oo)\_______

(__)\ )\/\

||----w |

|| ||

Being HPC compatible, singularity containers are also supported by a wide range of workflow management tools. For example, both snakemake and nextflow support job-specific singularity containers. This makes singularity containers uniquely suited for parallelizing workflows on HPC systems using the widely used slurm workload manager. Using singularity, containers and snakemake/nextflow is a way of scaling reproducibility to a massive scale. Furthermore, as an added benefit, bringing workflows from a desktop machine to an HPC system no longer requires writing custom job submission scripts.

Long-term Storage of Container Images¶

It is important to note that a mere container recipe file is not reproducible in itself since the build process depends on various (online) sources. Thus, the same recipe file might lead to different images if the underlying sources were updated.

To achieve true reproducibility, it isimportant to store the actual container images. For singularity images, this is particularly easy since an image is simply a large file. These can vary in size, from a few tens of megabytes (micro-containers) to several gigabytes, and are therefore not suited for being stored in a git repository themselves A free, citable, and long-term solution to storing container images is zenodo.org which allows up to 50 Gb per repository. Since zenodo mints DOIs for all content uploaded, the images are immediately citable. In contrast to Docker Hub (which also only accepts docker images), zenodo is also clearly geared towards long-term storage and discoverability via a sophisticated metadata system. Thus, it is ideally suited for storing scientific containers associated with particular analyses since these tend to not change over time.

Words of Warning¶

Even though singularity and docker might look similar, they are conceptually very different. Besides the obvious fact that singularity does not require root access to run containers, it also handles the distinction between the host and container file system differently. For instance, by default, singularity includes a few bind points in the container, namely:

$HOME/sys:/sys/proc:/proc/tmp:/tmp/var/tmp:/var/tmp/etc/resolv.conf:/etc/resolv.conf/etc/passwd:/etc/passwd$PWD

Note, $PWD comes in handy since it implies that all files in the working directory are visible within the container.

Binding $HOME by default, however, also implies that software using configuration files from $HOME might behave unexpectedly since the image specific configuration files are overwritten with the current users settings in $HOME.

While this behaviour is handy in HPC scenarios, it is potentially dangerous for reproducible research.

To avoid potential issues, any software installed in a singularity container should be pointed to a global, user-independent configuration file.